After finally beginning to find their footing following the Great Recession of 2008 and having built up their state rainy day funds, states are now finding that it’s not just raining — they are facing a tsunami. With their two main sources of revenue, the income tax and sales tax, both seriously impacted by the historic levels of unemployment claims and shuttered businesses, states are just beginning to try to manage a budgetary storm that could have lasting impacts on their economies. And while some lessons from the most recent recession may help in their recovery, the continuing unknowns from the pandemic will be difficult to measure.

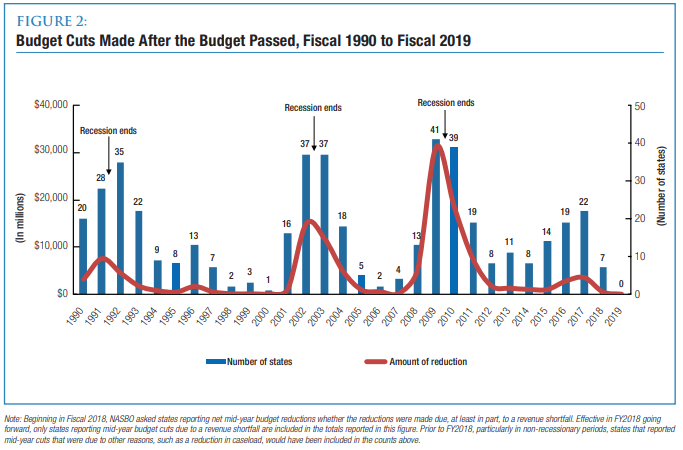

The last three recessions indicate that it will take a considerable amount of time just to get back to pre-recession revenue levels.

“The longest economic recovery in U.S. history has ended…that is clear,” said Barbara Rosewicz, Pew’s project director of research and content, state fiscal health, in a conversation this week with SSTI.

Rosewicz noted that the pandemic hit just as states were closing out their current fiscal years and considering their upcoming budgets. In addition to the hits on income and sales tax revenue, once the federal government changed the deadline on tax returns to July, many states followed suit, pushing tax income into the next fiscal year, further disrupting revenue expectations.

Figures for this week’s jobless claims topped another 4.4 million, bringing the total for the past five weeks to more than 26 million. Already, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that his state is in a “pandemic-induced recession,” and tasked an advisory committee to come up with short, medium and long term plans for economic recovery. States across the country are revising revenue projections, with New York estimating tax revenue would be between $4 and $7 billion below projections for FY 2020. Pennsylvania used two scenarios for business closures and projects revenues falling by $2.7 billion and $3.9 billion. Early estimates reveal that shortfalls could total more than $500 billion across the states.

Rosewicz called this a time of “really hard decisions.” Recessions play out differently, she said, and oil-dependent states will take a double whammy in this crisis as the oil market continues to weaken. States will be affected differently depending on their tax structures and how long the shutdowns continue. Those that are able to open their doors sooner should have more economic activity than those that are more deeply affected by the coronavirus.

However, Rosewicz, who has been analyzing state budgets since the last recession, said states did learn from that downturn and were able to build their rainy day funds in anticipation of another recession.

Some states are already taking measures to deal with this crisis, built on the lessons of the Great Recession. One tool states turn to is holding down on spending, Rosewicz said, along with freezes in hiring state personnel and possible even layoffs. States will also be able to pull from unspent general funds. Another option to increase revenue would be tax increases, but Rosewicz said states have not yet pulled that lever. And the Federal Reserve Bank has for the first time said it would buy bonds directly from the states, opening a borrowing channel for states that was previously unavailable.

As part of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act of March 18, the federal government increased the federal matching assistance percentage for Medicaid by 6.2 percentage points, which will be available as of Jan. 1, 2020, and will remain available for the duration of the emergency. The Congressional Budget Office estimates this will increase direct spending by about $50 billion over the 2020-2022 period, which will also aid states.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) enacted on March 27, 2020, provided $150 billion to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments to offset expenses stemming from the pandemic, but it allotted no money to offset the deepening state revenue shortfalls.

States were slowly rebuilding following the Great Recession. State budget officers and legislators were aware of the economic cycle and trying to prepare for the inevitable downturn. As states began their budget process this year they were anticipating revenue growth. In 2019, 46 states reported that FY 2019 general fund revenue collections exceeded original budget projections, the most states to do so since fiscal 2006, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers. On top of that, the median rainy day fund balance as a share of general fund spending reached 7.6 percent in fiscal 2019, which was a new all-time high.

A story as recent as December from Bloomberg noted that, “The stockpiles will be crucial to helping state governments avert the kind of steep budget cuts, layoffs and tax increases that followed the downturn set off in 2007 by the housing market crash.” The conjecture was that, despite an increase in spending by the states, they would be better prepared for another recession. However, a pandemic that has resulted in historic levels of unemployment claims and shuttered businesses is not something the states were planning for. Instead, states are already dipping into those reserves and expecting that those stockpiles will be gone in a matter of months.

The recovery from the last recession took longer than the previous two recessions, taking five years for states overall to get back to the level it had been at its peak before revenue fell in the Great Recession, Rosewicz noted. There was also great diversity among the states in how long it took to recover, she noted. As of the third quarter of 2019, 44 states had tax revenue that surpassed where it had been pre-recession, and six states that were below. Some of those had had artificial peaks prior to the recession, such as Alaska who had a big jump in production and high prices for oil.

The National Governors Association and the National Association of State Budget Officers both sent letters to congressional leaders requesting additional funds to offset state budget shortfalls, with the NGA specifying $500 billion. However, the latest funding package does not allocate any new money for state and local governments, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has indicated it will be at least May before Congress will consider such action. Without such support, the governors warn that economic recovery will be hampered. McConnell said in a radio interview this week that he preferred states pursuing bankruptcy protection than funding from the federal government.

Rosewicz said the future will be a time of “really hard tradeoffs, almost undoubtedly spending cuts, possibly tax increases, although those tend to come a little later….” She said that money for new projects will be put aside as states need to maintain basic services.

“Balancing the budget is going to be the name of the game,” she said.

Whether Congress gives states more flexibility in using the aid they have already been given may help, but she noted that when state leaders of both parties have told Congress they still need $500 billion, there is a real need present. If they don’t receive the money from federal sources, “they will have to fall back themselves and there’s a downside,” she continued. “When states have to either do spending cuts or tax increases, it takes money out of the economy and actually has the effect of lengthening the national recession. It’s not a pretty picture.”